The scene above is from a view point on Campbell’s Hill, southeast of the village of Scotsburn. It is a spring day in which the leaves are just beginning pop out. In the near distance is the tower on Bethel Presbyterian Church. A bit further in the view is a ridge adorned with farms in the community of Heathbell. In the distance is the blue waters of the Northumberland Strait and, on the horizon, the eastern end of Prince Edward Island. It is a peaceful spot that gladdens the soul.

It was not always that way. In 1819, a few dozen feet from this viewpoint, the most horrendous murder in Pictou County, (at least up until 1877), was committed.

This farm was first settled by a Campbell family, probably around 18031. They were from Rogart in Sutherland. The next farm up the hill was also settled by a Campbell family2, most likely a sibling or near relation. The names of the parents are presently unknown. Their graves, whether in Scotsburn or Durham, are unmarked. The mother died before 1819 after which the father took a second wife, also a Campbell, who was part of a Campbell clan on Scotch Hill. Of the first marriage, we only know of one son – Donald – the principal character in this story.

George Patterson in his 1877 publication The History of the County of Pictou, describes the events which I will paraphrase here.

Donald Campbell, then settled in the Earltown district, was returning from errands in Pictou and took the opportunity to stop at Campbell’s Hill to visit his father and stepmother. It is unknown whether something was said during the visit to upset Donald or if he was already angry when he stopped for a visit. It is believed that Donald resented the second wife of his father as he felt she was going to delay or diminish his eventual inheritance. The visit ended with Donald resuming his trip back to Earltown. He stopped at various farms between Campbell’s Hill and West Branch, giving the impression that he was trying to get home to Earltown before it became late.

However, Donald retraced his steps back to Campbell’s Hill after dark. He fastened the door of his father’s log cabin with withes attached to the latch handle to prevent the occupants’ escape and then set fire to the cabin while his father and stepmother were asleep. Awakened by the fire, the father managed to force the door open and started to remove the contents. Donald, lurking in the dark, struck the father with a stick and pushed him into the flaming house where the bones were found the next day. While this was unfolding, the stepmother managed to get out. She was a sturdy woman and would have won a fair fight, but was struck down by Donald’s weapon. He only partially succeeded in putting her into the flames, as she was “quite a load” to borrow an old phrase.

Hearing shouts and seeing the fire on the crest of the hill, a MacIntosh neighbour arrived to see a man fleeing whom he then believed to be a ghost. A small dog was also found at the scene which belonged to Donald and later aroused suspicion.

The remains were buried without an investigation. At the funeral, Mrs. Campbell’s brother, Angus Campbell, expressed his belief that there had been foul play. The authorities opened a case, exhumed the body of Mrs. Campbell, and determined she had been dealt a deadly blow. The scene of the crime was examined where a missing button from Donald’s coat was found as well as a flint that matched a gun Donald owned. It was suggested that Donald lost the flint, causing him to resort to using a bludgeon. Upon arrest in Earltown, it was noted that Donald had scorch marks on himself.

The subsequent trial received considerable attention. S.G.W. Archibald of Truro presented the case, which was adjudicated by a jury with Judges Haliburton and Wiswall presiding. Archibald presented a strong case after which the jury was quick to find Donald guilty. He was immediately sentenced “to be taken from where you now are to Prison whence you came and from thence to the place of execution and there hung up by the neck until your body is dead”. A clerk later noted: “Exactly a week later on the 22nd September Campbell was executed at Rogers Hill within a few yards of the spot where the crime was committed, pursuant to a warrant from the Earl of Dalhousie, our Lieut. Governor”.

Executions were a spectator sport in those times, appealing to the darker side of the human spirit. On the appointed day, Donald was loaded on a cart and transported to the Kirk then located beside St. John’s Cemetery. This was the end of a proper road. Access to points beyond was by way of paths. Guarded by the militia and accompanied by a group of clergymen, the procession climbed the 3 km path to the remains of the incinerated cabin. Once at the scene of his crime, Donald confessed to his crime but showed no interest in repentance despite the efforts of Rev. Dr. James MacGregor and other clergy.

The execution was supervised by the High Sheriff of Halifax County. The ineptitude of the chosen executioner added to the drama. Hanging, despite the image it conjures, was somewhat merciful. The process involved releasing a trap door or a push off the gallows platform. The sudden drop of the body would cause the noose to break the neck, thus bringing instant death. In this case, the bolt on the trap door didn’t release fully thus causing the rope to slowly tighten instead of snapping the neck. The result was death by a slow strangulation 3. So disturbing was the spectacle that many in attendance vowed never to view another hanging.

Patterson was silent on the particulars of Donald’s own family and life back in Earltown.

Two and one half kilometers east of Earltown Village on the Berichon Road, an old road branches to the north. This was once a listed shortcut between the Berichon and Clydesdale. (It is now gated by the owner of the surrounding woodland). About 250 meters in, a logging road branches northwest into a grown-over clearing. A few meters off this road is the cellar of Senoid Sutherland. Senoid is Gaelic for Janet and is pronounced Shawna, which morphs into Shawney, the equivalent of Jennie. This farm was once known as the Shawney place4.

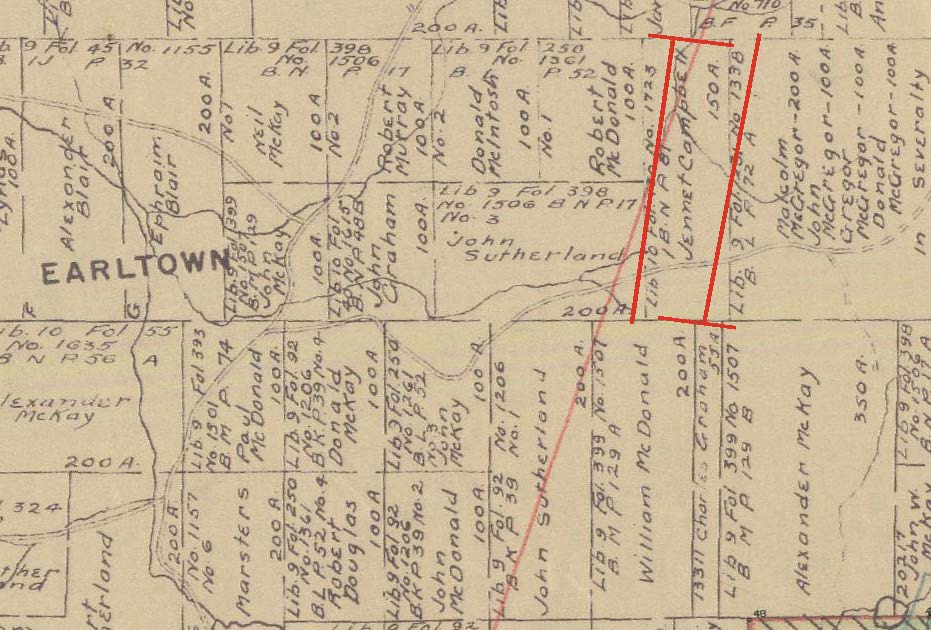

The land grant map found online shows this to be the 150 acre grant to a Janet Campbell. Another version of the land grant maps show it to be the grant of Donald Campbell. Some deeds of surrounding properties reference the line of Janet Sutherland while others state Janet Campbell.

This confusion of names confirms the oral tradition around Earltown that this property was that of Donald Campbell, convicted killer. It also confirms another interesting story that Donald’s widow, in shame and horror, changed her surname and those of her children to Sutherland to distance themselves from the crime at Campbell’s Hill.

Sutherland was Janet’s maiden name. There is a tradition that she was connected to John Sutherland “Doula” who settled an adjoining farm but the connection has yet to be confirmed. She was born in Sutherland and came to Nova Scotia prior to 1815. She had at least one brother in the Scotsburn area who gave evidence at Donald Campbell’s trial.

Janet and Donald’s eldest son, John, was born at Rogers Hill in 1816 which would place their marriage around 1814-15. Janet’s eventual land grant was among those petitioned by a group of second generation immigrants living at Rogers Hill. These petitions were in 1817, suggesting that Donald and Janet may have begun clearing their farm that summer. The deeds would not be granted until later in the 1820’s hence Donald’s name is absent. A second son, George, was born in 1818 at Earltown.

It is hard to imagine the situation that Janet found herself in on that 22nd day of September, 1819. Widowed, two children ages 3 and 1, a crude log cabin, a partially cleared farm, no immediate family in close proximity, and an epic scandal to overcome. Donald Campbell was characterized as an ignorant and unsavory character with obvious violent tendencies. The scandal may have been a blessing. Domestic abuse is as old as matrimony.

A return to the Rogers Hill area was not likely an option given the circumstances. Earltown was still in infancy and new settlers were arriving with no ties to the victims or accused. It would appear that Janet stayed on course and made the small farm work. Undoubtedly, there would be some assistance from siblings in Roger’s Hill, possibly a kind father was still living. The Highland culture ensured that widows had help. Hard labour, such as the annual threshing and wood cutting, was often a collective labour in the neighbourhood. It must be remembered that back in Scotland, the women were the gardeners and looked after the dairy livestock.

The 1838 census confirms that “Widow Sutherland” with two males over 14 were still living on the Berichon Cross Road. The next census in 1861 finds her son John as the head of household, which indicates that Janet had passed away in the intervening years. No tombstone marking the grave of either Janet Sutherland or Janet Campbell exists but she most certainly rests in the village cemetery.

The eldest son John took over the homestead. In 1857 he married Catherine, daughter of “Laughing” Sandy Sutherland and Christy Baillie of The Falls. They had one daughter Betsy. John’s brother George is absent from the farm in 1871 but returned in 1881. When John died in 1885, he left the farm to George with the stipulation that Catherine be provided a living for as long as she would live. By 1911, both George and Catherine are absent from the census. As for John and Catherine’s daughter Betsy, we have no further information.

The property was later purchased by George MacIntosh. It is a short distance through the woods to the main MacIntosh farm on the Denmark Road. The Shawney place continued to used for pasture and crops by the MacIntoshes and later the Van Veld family.

Sources:

Patterson, George “Old Court Records of Pictou County, Nova Scotia published by The Canadian Bar Review, Vol13 No 3 1935

Patterson, Rev. George A History of the County of Pictou, Nova Scotia Dawson Bros, Montreal 1877

Gladys Sutherland MacDonald – Interview – 1978

A. Howard Murray and Mary Douglas Murray – Interview – 1978

Layton Lynch – assistance in locating the Campbell – Sutherland homestead in the Berichon.

- The Dunwoodie family were the next to occupy this farm for a couple of generations. After the farm was vacated, James and Harold Forbes of Lyon’s Brook farmed it for many years. ↩︎

- The farm owned by Hugh and Stanley Campbell in the mid 20th century. ↩︎

- The executioner was brought by the Sheriff from Halifax. Pictou had its own executioner at the time who served the courts in Prince Edward Island as nobody on the Island would accept the responsibility. ↩︎

- The current owner has it gated to keep out traffic. His number is posted on a sign for people to call for permission to enter. ↩︎