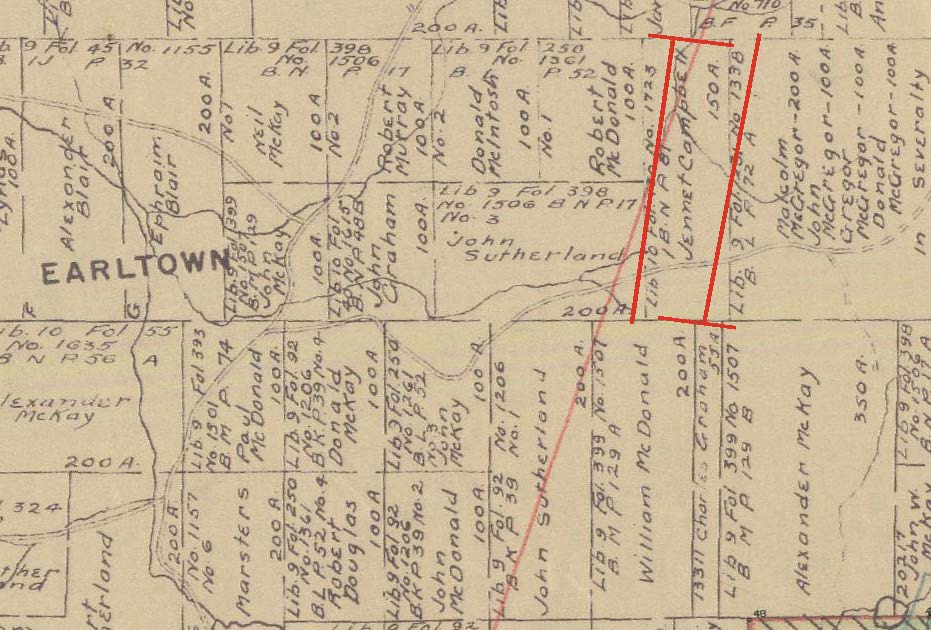

Many will recognize the house in the above picture as the home of Reta and Harvey MacRae, Kavanagh’s Mills. Although in the New Annan district for the past 150 years, it was originally in the District of Earltown. Local politics, explained here, changed the boundaries in 1858. It has been continuously in the Murray family since 1832 and owned by extended family prior to that.

The ship Hector, often considered the Mayflower of Nova Scotia among Scots, arrived in Pictou Harbour in 1773 carrying migrants from the North of Scotland. Although not the first to settle in Pictou County, they were the first of a mass migration of Highlanders to the north counties of Nova Scotia in the following 75 years. Some accepted their fate on the lower reaches of the three rivers of Pictou, while others went on to more settled parts of the province where they could find work while establishing homes. None of these passengers settled in the Earltown area. It would be 40 years before Earltown opened up for settlement. However, seven offspring of passengers did find their way to the western boundary of Earltown.

They bore the name Crowe but were children of Abigail Murray, the 16-year-old daughter of James Murray and Lillian Sutherland, who is found on the list of Hector passengers with her parents. The Murrays were from Sutherlandshire, some say Rogart but we will likely never know. They did not suffer in Pictou for long and instead proceeded overland to Truro, eventually establishing a home in the Portaupique area. Abigail married Aaron Crowe, Irish by birth and one of several of that family to settle in the Onslow Township. Abigail and Aaron settled on a farm at the mouth of the North River, which is now a trendy family amusement venue each autumn.

Three of Abigail’s sons moved to the Tatamagouche Mountain and Kavanagh’s Mills area around 1820. George and Aaron settled on the ridge near the Tatamagouche Mountain Cemetery. John acquired what was later the Murray property from the original grantee. George and Aaron are the ancestors of the present day Crowes in North Colchester. John died in 1828 unmarried.

Three daughters of Abigail found their way to the area. Elizabeth married Richard Hyslop, a Dumfries native who emigrated to Onslow. They settled the property to the north of the Murray – MacRae farm which remained in the family until the last of the descendants died in the 1930’s. Christiana Crowe married Ebenezer Cock of East New Annan. They started a farm but decided to return to the more established settlement of Onslow.

Abigail’s eldest daughter Sarah was the last to arrive in the area. She was married to another Hector descendant, William Murray. This couple is the focus of this post.

William Murray, often called Old Willie Murray, was the son of Hector passengers, Walter and Christianna (Sutherland) Murray. He was born around 1777 when his parents were living on their first farm on the site of the present-day town of Trenton. His father, Walter, had been a soldier in the British army and had served for some time in India. After a short tenure on the East River of Pictou, Walter moved his young family by boat eastward down the coast to a sizable grant near the mouth of Barney’s River. Murray’s Point Cemetery is located on the waterfront of his grant.

In addition to the shoreline grant, the old soldier nabbed a 500 acre grant further up Barney’s River near the community of Avondale. It was here that his son, Old Willie, established a homestead and at a later date, a mill. Not content with local prospects, he went far afield to Onslow for a bride. Sarah Crowe, as already noticed, was the granddaughter of James and Lillian Murray of Hector fame. While documentary proof is scarce, William and Sarah were most likely near cousins[1], the two families maintaining contact through kinship despite being a considerable distance apart.

The year 1832 brought many changes to the family. Son Alexander was killed when felling a tree on the family farm within weeks of marrying Mary MacDonald. That same year, the family mills burned down. Whether the motivation was grief over the death or the loss of the mill, William, Sarah and at least the two younger children packed up and moved to Kavanagh’s Mills. A deed was registered that year between John Crowe, (or estate), and William Murray. The farm was next to the water powered mills at the Kavanagh’s Mills bridge. William, a millwright by trade, likely upgraded the original mill and operated it for a few years[2].

It is believed that a portion of the present house at Kavanagh’s mills dates back to the 1830’s.

William and Sarah had a family of nine:

- Walter 1799-1888 settled at Port Richmond, Cape Breton, and was a mariner. He was married to Amelia Grant of Lower River Inhabitants. They had at least seven children, four of whom were seaman who died in a shipwreck on Devil’s Island, Halifax Harbour, in December of 1859.

- James W. (Old Jimmie) 1799-1899 was a blacksmith at Avondale and married Margaret Grant.

- David 1802-1888 was a sea captain out of Mulgrave and married three times. He also devised a water utility to service ships passing through the Strait of Canso.

- John G. 1805-1877 was a mariner and, like Walter, an original grantee at Port Richmond. He was married to Catherine Grant.

- Andrew 1805-1886 appears to have come to Kavanagh’s Mills with his parents and shortly thereafter married Martha Ann Wortman, daughter of Jacob Wortman, Corktown. They lived for a time in Onslow before moving to the Upper Saint John River valley. They both died in Easton, Maine.

- Alexander 1809-1833 , noticed above, married Mary MacDonald of Avondale.

- William Murray 1811-1879 remained in the Barney’s River area where he married Margaret MacDonald of Merigomish. They eventually joined Old Willie at Murray’s Siding.

- Elizabeth 1815-1884 married Jacob Wortman, Jr. in Corktown. They brought up ten children in Corktown. In their later years, they joined family members at North Bend, Wisconsin.

- Aaron 1817-1894 took over the Kavanagh’s Mills farm where he lived most of his life.

William moved on to other ventures, leaving the farm to Aaron. It is believed that he spent a brief period at Beaverbrook before settling at Salmon River on the Greenfield Road. Here, he built another gristmill. When the Intercolonial Railway was constructed through the community, a siding was placed near the bridge across the Salmon River. It was named the Murray Siding and the name was later applied to the surrounding community.

Sarah died at Murray’s Siding in 1850 and William in 1855. They are buried in the Onslow Island Cemetery. Son William took over the home place at Murray Siding.

Aaron, who continued with the Kavanagh’s Mills property, married Jane Wilson. She was born at the head of the Chiganois Marsh near Belmont in 1818 to Henry Wilson and Esther Staples. Her mother died when she was only six years of age. It appears that Jane may have been put in the care of relatives in North Colchester. Two of her aunts were married to Aaron’s uncles, George and Aaron Crowe.

They raised nine children at Kavanagh’s Mills:

- Walter died young

- William married Rebecca Crowe and lived in Truro

- Henry was a commercial traveler in the region. He married Mary Ann Benvie of Sheet Harbour. It was not a happy situation and the marriage dissolved. Their three children lived in Nevada. Henry retired to Kavanagh’s Mills where he died in 1920.

- Alice married James Henderson of South Tatamagouche where they lived for a number of years. She died in Bridgewater, Minnesota, where some of her children had settled.

- Davidson married Letetia Crowe and lived in Beaverbrook. His descendants are to be found in the Masstown area.

- George Murray left home young and was not heard from thereafter.

- Robert Murray also left home young and was not heard of for many years. Around the time of his parents’ deaths, he made contact. He had settled in Los Angeles.

- David 1859-1927 more later

- Alexander Fitzpatrick 1864-1936 like many of his neighbours and relatives, went west and settled in Sandstone, Minnesota.

David “Dave” Murray took over the homestead and looked after his parents. In 1894, he married Annie Baillie of West Earltown. In addition to farming, Dave gathered milk around East New Annan and Tatamagouche Mountain for the cheese factory in Balfron. Annie ran a postal desk for the neighbourhood in her kitchen. She was also called upon as a midwife.

While growing up relatively close to each other, they came from different backgrounds. Dave was unilingual and not much for the Highland love of entertaining. Annie’s first language was Gaelic which was the “go to” tongue when hosting her family and friends from Earltown.

David and Annie (Baillie) Murray with daughter Jean.

Dave and Annie had two daughters. Jean 1897-1974 was a teacher in the surrounding communities before marrying Harry Langille of Central New Annan. Alice Marguerita, aka Reta, 1903-2000, lived all but the last couple of years of her life on the old Murray homestead. She married Harvey MacRae of Nuttby. The old homestead is still owned by a family member after one hundred and ninety three years.

[1] There is an oral tradition that Walter and James Murray were brothers. That would make William and Sarah first cousins once removed. That relationship between spouses was not uncommon in those days.

[2] This farm was originally granted to Daniel Eaton of Onslow on the premise of establishing a grist mill to serve East New Annan, Tatamagouche Mountain and West Earltown. He didn’t leave a footprint on the area and it would seem that John Moore, married to Susan Harris, may have built the original mill as the brook has carried the name Moore’s Mill Brook. John Crowe is also mentioned in certain documents as a miller.